What Percent of the Biomass Produced in a Forest Is Returned to the Soil?

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Effect of disturbance on biomass, production and carbon dynamics in moist tropical forest of eastern Nepal

Woods Ecosystems volume 3, Commodity number:11 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Forest biomass is helpful to appraise its productivity and carbon (C) sequestration chapters. Several disturbance activities in tropical forests have reduced the biomass and net primary product (NPP) leading to climate change. Therefore, an accurate estimation of forest biomass and C cycling in context of disturbances is required for implementing REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Woods Degradation) policy.

Methods

Biomass and NPP of trees and shrubs were estimated past using allometric equations while herbaceous biomass was estimated by harvest method. Fine root biomass was adamant from soil monolith. The C stock in vegetation was calculated by multiplying C concentration to dry out weight.

Results

Total stand biomass (Mg∙ha–1) in undisturbed forest stand (United states) was 960.4 while in disturbed wood stand (DS) it was 449.1. The biomass (Mg∙ha–1) of trees, shrubs and herbs in US was 948.0, iv.4 and 1.iv, respectively, while in DS they were 438.4, 6.1 and i.2, respectively. Total NPP (Mg∙ha–1∙twelvemonth–ane) was 26.58 (equivalent to 12.26 Mg C∙ha–1∙yr–1) in The states and fourteen.91 (6.88 Mg C∙ha–1∙yr–1) in DS. Full C input into soil through litter plus root turnover was 6.78 and 3.35 Mg∙ha–ane∙year–1 in US and DS, respectively.

Conclusions

Several disturbance activities resulted in the significant loss in stand biomass (53 %), NPP (44 %), and C sequestration capacity of tropical forest in eastern Nepal. The net uptake of carbon by the vegetation is far greater than that returned to the soil by the turnover of fine root and litter. Therefore, both stands of present forest act equally carbon accumulating systems. Moreover, disturbance reflects higher C emissions which can be reduced by better management.

Background

Tropical forests play an important role in the global C cycle. They contain about 55 % of global forest C (Pan et al. 2011) and account for 34 % of terrestrial gross principal production (Beer et al. 2010). Carbon is stored in forests mainly in biomass and soils. The C dynamics of a forest reflects ecology conditions such as climate, soil, structure, nutrient availability and disturbance (Chave et al. 2001). Woods disturbances often lead to the changes in species composition, structure, stand biomass, productivity and C cycling. Therefore, a pocket-sized disruption in tropical forests might result in a significant change in the global C cycle.

Biomass and production are important parameters for understanding the performance of a wood ecosystem. Studies on biomass assist to assess the effect of disturbances on productivity, C dynamics, food cycling and stability of forest stands. Principal production is normally regulated by the availability of nutrients. Decomposed fine roots and aboveground litter are the sources of nutrients in the soil. The contribution of fine roots in the C and nutrients input to soil is equivalent or even higher to that from leaf litter in tropical moist forests (Roderstein et al. 2005).

Precise quantification of forest biomass, product, and C stock demands the conscientious interpretation of both the aboveground and belowground aspects. Despite this requirement, near of the past studies in tropical forests are constitute to be limited to analyzing the aboveground systems (Chave et al. 2008; Djomo et al. 2011; Malhi et al. 2011; Doughty et al. 2013; Ngo et al. 2013; Girardin et al. 2014; Malhi et al. 2014) and only a few studies concern to the belowground aspects (Ibrahima et al. 2010; Powers and Perez-Aviles 2013; Noguchi et al. 2014).

In Nepal, only few studies have been conducted regarding the biomass, production, and C sequestration in tropical forests (Mandal 1999; Baral et al. 2009). More than data is required to sympathize the structure and functioning of the forests. Nowadays written report was designed in tropical forest of eastern Nepal with the following specific objectives: a) to estimate the biomass and production of herb, shrub and tree species; b) to find out the event of disturbance on biomass, production and C dynamics.

Methods

Study area

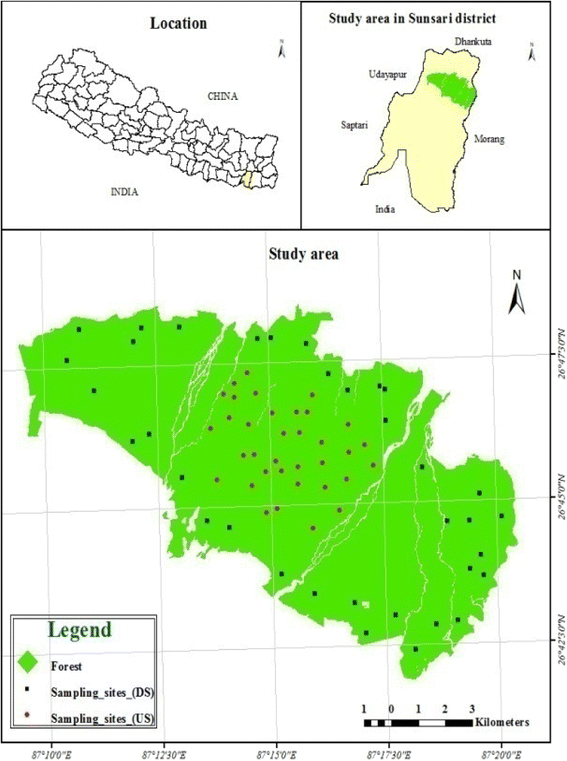

The written report was conducted in a Sal (Shorea robusta) dominated moist tropical forest of Sunsari District, eastern Nepal (breadth 26°41'N to 26°50'N and longitude 87°09'E to 87°21'E), within the altitude range of 220 to 370 m above msl (Fig. 1). The forest lies in the catchment area of Koshi River, one of the largest rivers in Nepal. The total area occupied by the forest is 11394 ha.

Location of the study woods in eastern Nepal and the sample plots

The central part (core area) of the forest is relatively undisturbed, while the peripheral part is affected by disturbance activities as removal of timber, livestock grazing, fuel-wood and litter collection, tree lopping, removal of poles for house-hold constructions and forest fires. These disturbances take caused deforestation, forest fragmentation and deposition and subsequent invasion of exotic species like Mikania micrantha, Lantana camara, and Chromolaena odorata, which adversely affect the native plant variety in the forest.

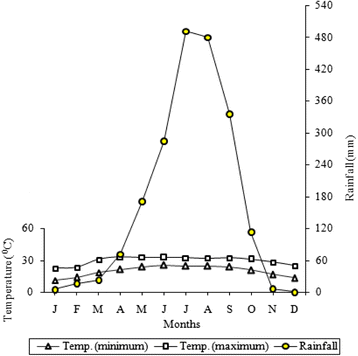

The climate is tropical and monsoon type with three singled-out seasons: dry and warm summertime (March to May), moisture and warm rainy (June to October), and dry and cool winter (November to February). The hateful monthly minimum and maximum air temperature during 2005–2014 ranged from ten.9 °C to 25.three °C and 22.vi °C to 33.ii °C, respectively. The average annual rainfall for the period was 1998.6 mm (Fig. two). Relative humidity was higher in rainy season with highest value in August (92 %).

Ombrothermic representation of the climate in tropical moist forest region of eastern Nepal. The data pertain to the period 2005–2014

The forest is bordered by the Siwalik loma in the northward and the Gangetic alluvial plains in the s. The expanse has been formed from soft erodible sediments of the Siwaliks and is characterized by the presence of boulder beds mixed with sand, silt, dirt imparting a porous nature. The soil mainly consists of deep alfisols.

The forest tree layer is dominated by Sal. Other main associates are Haldina cordifolia, Lagerstroemia parviflora, and Terminalia alata. Clerodendron viscosum and Murraya koenigii are some of the main shrub species while Chromolaena odorata and Achyranthes aspera are dominant herbs.

Institute biomass estimation

The forest was divided into 2 parts: i) the relatively undisturbed core expanse (treated as undisturbed stand; United states), and ii) the disturbed peripheral area (treated as disturbed stand; DS). Because of the following characters the cadre area was considered as US: canopy area ranged betwixt 153.8 and 226.9 m2, crown embrace ranged from 70–80 %, density of the tree was 466.4 individuals∙ha−ane and tree stumps were absent-minded. The peripheral role of the forest is disturbed because of following characters: canopy area ranged between 28.3 and 77.5 thoutwo, crown cover ranged from 30–40 %, tree density was 234.3 individuals∙ha−1 and tree stump density was lxx stumps∙ha−one.

The tree biomass contained inside US was estimated using 35 randomly established sample plots of 20 one thousand × twenty m size determined by species-area curve method. Same size was applied for DS as well. For the estimation of shrub and herb biomass nested quadrats of 5 m × five 1000 and one m × 1 m were used, respectively. Girths of all the copse (>10 cm gbh) at breast summit (one.37 cm above the soil) and of shrubs (10 cm above the basis level) present in each of the sample plots were measured. Density (individual per hectare) and basal expanse (girthii∙(4π)−one) of the trees within plots were adamant. Biomass of trees was estimated by using girth:biomass allometric equations (Singh and Singh 1992; Mandal 1999). For estimating coarse root biomass, root:shoot ratio of 0.21 proposed for lowland tropical forests was used (Malhi et al. 2009; Malhi et al. 2014).

The aboveground herbaceous biomass present in the sampling plots was harvested twice, in summer (May 2012) and at the cease of rainy season (September 2012). Summer and rainy season values were averaged to obtain almanac mean herbaceous biomass.

Fine roots (<5 mm diameter) were collected from seventy randomly established sample plots, thirty v each in U.s.a. and DS. Fine root biomass (FRB) was determined from soil monolith (10 cm × ten cm × 30 cm), divided into two depth ranges (upper: 0–xv cm and lower: 15–thirty cm) at each sample plot in summer (May 2011), rainy (September 2011) and winter (Jan 2012) seasons. Summer, rainy and winter flavor values were averaged to obtain annual mean FRB.

Litterfall and litter mass

For the estimation of litterfall ane litter trap (1 m × one m) was fixed on the forest flooring at each of the seventy sampling plots. Litterfall was collected at monthly intervals from April 2011 to March 2012 and categorized into leaf and non-leaf components. Litter mass accumulated at each sampling plot was collected once every flavour from ane 1 k × one m plot. The turnover rate of litter was calculated co-ordinate to Jenny et al. (1949).

Internet product

Using the allometric equations, the aboveground biomass (AGB) of different components of marked trees/shrubs in permanent sampling plots was computed for 2011 (B 1) and 2012 (B two) from respective girth measurements. The cyberspace changes in biomass (ΔB =B 2 – B i) of components yielded almanac biomass increments which were summed to get the net AGB accretion in the trees/shrubs. Aboveground herbaceous net production was estimated every bit the differences between maximum and minimum biomass values through the twelvemonth.

The almanac leaf fall was added to the foliage biomass accumulation to stand for leaf product, and wood and miscellaneous litterfall values were added to the biomass accumulation in twigs (Singh et al. 1994). Coarse root production was estimated as a fraction of stalk production (Malhi et al. 2009; Malhi et al. 2014). Fine root production (FRP) was estimated equally the differences betwixt maximum (rainy flavour values) and minimum (summertime season values) biomass values. The fine root turnover was calculated as a ratio of its production and annual hateful biomass (Srivastava et al. 1986).

Carbon estimation in vegetation and litter

Samples of different tree, shrub and herb (aboveground) components of all species were collected from each sampling plot. The litter (leaf and non-leaf) and fine root (< 2 and ii–v mm diameter) samples were also collected. All the samples were oven dried at fourscore °C to constant weight, powdered and used separately for C analyses.

Carbon present in plant materials was estimated by ash content method. Carbon concentrations were assumed to be approximately 50 % of ash free weight (McBrayer and Cromack 1980). In this method oven dried plant components (stem, branch, root, leaf, and litter) were burnt separately in electric furnace at 400 °C. Ash content (inorganic elements in the form of oxides) left after burning was weighed and carbon concentration was calculated by using the following equation:

$$ \%\ \mathrm{Carbon} = \left(\mathrm{Initial}\ \mathrm{weight}\ \hbox{--}\ \mathrm{Ash}\ \mathrm{weight}\right)\times 100\kern0.1em /\kern0.1em ii $$

(1)

The C stock in vegetation was calculated by multiplying C concentration (a conversion factor) to dry weight. A conversion factor of 0.470 was used to convert aboveground and coarse root biomass to C. To obtain C stock in fine roots a conversion factor of 0.430 and 0.455 was used for < 2 and two–5 mm size class, respectively. The conversion factors of 0.453 and 0.468 were used for leaf and not-leaf litter, respectively.

Soil sampling and carbon estimation

Soil samples were nerveless from lxx randomly selected pots (35 each in US and DS). Soil was collected from three pits (10 cm × x cm × xxx cm each) from each plot. The soils of three pits were mixed and pooled as i replicate (Singh et al. 2001). Majority density (BD) was determined by using a metal tube while soil organic carbon (SOC) by dichromate oxidation method (Kalembasa and Jenkinson 1973). Carbon content in soil (Mg C∙ha−1 soil) was calculated using the formula:

$$ \mathrm{C} = \mathrm{S}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{C} \times \mathrm{soil}\ \mathrm{depth} \times \mathrm{B}\mathrm{D} $$

(two)

where SOC is soil organic carbon in % and BD is bulk density (g∙cm−3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were carried out in MS excel 2007 and SPSS (IBM Statistics, ver. 20) packages. All the information were usually distributed except that of basal surface area of trees which were log transformed earlier analysis. Pearson's correlation coefficients were obtained between normal and linear data of biomass, cyberspace production, stand density and basal area of trees. Students T-test was performed to compare the mean biomass and production of trees between The states and DS.

Results

Plant biomass

The biomass and C stocks of trees, shrubs, herbs and fine roots are summarized in Tables 1 and two. The estimated total biomass for the US was 960.4 Mg∙ha–ane (equivalent to 452.06 Mg C∙ha–1), while for DS information technology was 449.1 Mg∙ha–i (equivalent to 211.33 Mg C∙ha–1).

The full biomass (Mg∙ha–1) of the tree layer in US and DS was plant to be 948.0 and 438.4, respectively. The tree biomass in the US and DS was significantly different (P < 0.001 at 95 % confidence level). Of the full tree biomass, 83 % was aboveground and 17 % belowground (excluding fine root) in both the stands. The maximum contribution to tree AGB was fabricated past bole in both stands (64 % each) and minimum by foliage (2 % each in both stands).

The shrub biomass (Mg∙ha–1) showed increasing trend from four.4 at US to 6.1 at DS. Contribution of shrub biomass to the total stand biomass was college in DS (i.4 %) than U.s. (0.5 %). The aboveground herbaceous biomass contributed 0.one % in United states of america and 0.3 % in DS. The fine roots shared 0.7–0.8 % to total stand up biomass. The annual FRB was lower in DS by 49.5 %.

Litterfall

The total annual litterfall (Mg∙ha−1∙year−1) was 11.8 in The states and 5.4 in DS. Leaves accounted for 69 % (Usa) to 76 % (DS) of total litterfall while non-leafage litter formed the residue. The full litter mass (Mg∙ha−1) comprised 6.vii in Usa and 3.6 in DS. The turnover rate (per yr) of the total litter ranged from 0.79 in DS to 0.83 in US.

Net production

The total NPP (Mg∙ha–1∙yr–ane) of the forest was 26.6 (equivalent to an annual C sequestration of 12.26 Mg C∙ha–i∙yr–ane) in US and 14.9 (i.due east. vi.88 Mg C∙ha–1∙yr–ane) in DS (Table 3). Amongst the different life forms: tree, shrub, and herb comprised 72 %, 2 %, and 6 % of NPP in U.s.a. and 67 %, 5 %, and 9 % in DS, respectively; while rest 20 % NPP in US and 19 % in DS were contributed by stand fine root.

The contribution in NPP by different components of trees was in the guild leaf > bole > twig > coarse root > branch, in both stands (Table iv). The most prominent C sink was found to be leaf that deemed for 42–43 % of the total NPP. For shrub, maximum contribution to NPP was fabricated by stalk in both stands and minimum by foliage. The NPP of herbs (aboveground) ranged between ane.3 and 1.7 Mg∙ha–1∙yr–ane in DS and US, respectively (Table 3).

Full aboveground NPP (Mg∙ha–1∙twelvemonth–i) combining tree, shrub and herb were 19.93 in Us and 10.97 in DS. In belowground parts, percentage allocation of NPP was upwardly to 25 % of total NPP (26.58 Mg∙ha–1∙twelvemonth–1) in United states and 26 % (3.94 Mg∙ha–1∙yr–one) in DS (Table v). Of this, both tree and shrub's coarse root contributed near 21 and 26 % to total belowground NPP in US and DS, respectively; whereas fine root comprised about 79 % of belowground NPP in U.s. and 74 % in DS.

Because both depths, average turnover rate (per yr) of smaller fine roots (0–2 mm bore) was 0.75 in US and 0.86 in DS, whereas it was 0.74 and 0.76 for larger size form (ii–5 mm) in US and DS, respectively. The biomass accumulation ratio (biomass/net product) decreased to xxx due to the consequences of woods disturbance in DS, while this value was college (36) in United states. Net production of trees was significantly college in Usa than DS (P < 0.001). Positive correlations were found between stand density, basal area, biomass and NPP of trees in both stands (Table 5).

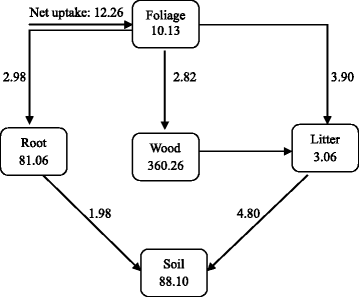

Carbon budget and flux

The dry matter values for standing crops, net product, litterfall etc. of both undisturbed and disturbed stands were converted to C (Figs. 3 and 4). Aboveground C storage in both stands was 82 % of the total C in vegetation and 64–69 % of that stored in stand (vegetation plus soil). The forest received a C input through NPP of 12.26 Mg∙ha–i∙year–1 in US and 6.88 Mg∙ha–1∙yr–1 in DS. Of this, 69 % was associated with aboveground and 31 % with root NPP in The states while in DS, contributions from aboveground and root parts to total NPP was 67 and 33 %, respectively.

Compartment model showing annual carbon budget for the undisturbed stand of the moist tropical forest of eastern Nepal. Values in 'tanks' represent boilerplate carbon content (Mg∙ha–1). The foliage compartment also includes aboveground standing crop of herbs, and the root compartment includes coarse roots as well as fine roots. Cyberspace annual fluxes between the compartments are given on arrows (Mg∙ha–1∙yr–1)

Compartment model showing annual carbon budget for the disturbed stand of the moist tropical forest of eastern Nepal. Values in 'tanks' represent average carbon content (Mg∙ha–1). The foliage compartment also includes aboveground standing crop of herbs, and the root compartment includes coarse roots every bit well every bit fine roots. Cyberspace almanac fluxes between the compartments are given on arrows (Mg∙ha–one∙yr–i)

Wood (bole plus co-operative) and roots accounted for 47 % (in Us) to 53 % (in DS) of the full C input, the remaining 53 % in US and 47 % in DS being utilized for the extension of the photosynthetic parts (tree and shrub leafage plus herbaceous shoots). The input from the leaf compartment to the litter compartment was 3.xc Mg∙ha–1∙year–1 (equivalent to 100 % of herbaceous aboveground product plus 86 % of foliage production) in Usa while it was 2.17 Mg∙ha–1∙year–ane for DS. About 14 % (0.51 Mg∙ha–i∙year–one in United states of america and 0.26 Mg∙ha–one∙year–i in DS) of foliage product did not notice its manner into leaf litterfall.

Carbon addition to the soil through the turnover of roots and aboveground litter amounted to 1.98 and 4.lxxx Mg∙ha–1∙yr–i, respectively in U.s.a. (fine root and litter turnover were 86 and 83 % per yr, respectively). Similarly, C input due to the turnover of roots and aboveground litter was i.05 and ii.30 Mg∙ha–1∙yr–one, respectively in DS (fine root and litter turnover were 82 and 79 % per yr, respectively). Apparently, contribution of belowground establish parts to soil C is substantial, representing 29 and 32 % of the full input in Us and DS, respectively.

Discussion

Biomass and production

The average biomass of the vegetation in both Usa and DS was 704.8 Mg∙ha–1 (331.seven Mg C∙ha–1). More than double biomass in United states as compared to DS may be related to the presence of more than trees of larger girth classes. The lower biomass in DS may be the result of lower density of copse (234 individuals∙ha–1) compared to US (466 individuals∙ha–1). It may also exist associated with disturbance activities similar tree felling and removing for timber, firewood collection, lopping, grazing, and selective logging.

Biomass allocated to shrub was higher in DS than US. It may be the effect of their ability to utilise the space and resource created past disturbances. The higher biomass of herbs in U.s.a. as compared to DS may be due to the nutrient rich soil at this stand up (Gautam and Mandal 2013). The different causes are put forward by different workers regarding the aggregating of biomass in the forest. Mean annual atmospheric precipitation explains 55 % of the variation in biomass in seasonally dry out tropical forests (Becknell et al. 2012). The bachelor nutrients, soil, land utilise history, species limerick and stand historic period are also responsible for the remaining variations (Powers et al. 2009).

Near of the C stock in the wood was associated with AGB (64–69 %). Belowground biomass and soil up to the depth of xxx cm contained 31 to 36 % C stock. Past study also institute 33 % C in top soil of 1 grand in primary tropical forest of Singapore (Ngo et al. 2013). Globally, tropical forests store about 50 % C in AGB and side by side 50 % within i m soil (Dixon et al. 1994). The contribution of these pools to the total C stocks varies amidst the sites. For case, an African moist tropical forest had more than three times as much C in AGB as in soil to 1 m depth (Djomo et al. 2011), while a Peruvian montane wood had twice equally much C in soil as in AGB (Gibbon et al. 2010). Ii Asian forests, a tropical seasonal forest in Communist china (Lü et al. 2010) and a lowland dipterocarp forest in Malaysia (Saner et al. 2012) store twice equally much C in biomass as in soil. The contribution of leaf fall to full litterfall in the present written report (69 % at United states of america and 76 % at DS) is in the range of by studies in tropical forests (72–74 %) (Girardin et al. 2014; Malhi et al. 2014).

The data obtained for NPP are comparable with the unlike tropical forests of world (Tabular array 6). Although having higher biomass, the NPP of present forest is relatively low indicating its maturity. Generally, in quondam growth tropical forests the NPP remains either stationary or decreases with historic period. The college NPP of some old tropical forests may be linked to forest dynamics. The more dynamic forests favor faster growing trees and species with lower biomass and maintenance costs (Malhi et al. 2009).

Aboveground NPP of Us (8.54 Mg C∙ha−1∙yr–1, excluding herbs) is comparable with the tropical forests of world while quite low than the eastern Amazonian forest (Doughty et al. 2013). Moreover, aboveground NPP of DS (4.54 Mg C∙ha−ane∙yr–1, excluding herb) is almost to paleotropical forests, and mean of the earth tropical forests. Equally far as the belowground NPP is concerned (i.77–2.98 Mg C∙ha−1∙yr–1), it is comparable to the Amazonian tropical woods (Table 6).

Disturbance affects the NPP either by increasing resource availability or through the changes in functional backdrop of customs. The disturbance results in canopy opening, which increases availability of light, favor new leaf product, and finally above-basis allocation increases (Aragão et al. 2009). Simply in the present study, per centum allocation to aboveground parts was virtually same in both U.s. and DS. Information technology may exist the outcome of severe lopping activities in DS, which is also indicated past less percentage of NPP allocation to twig and leaf, and higher percentage allocation to bole and branch in DS. Relatively higher pct of NPP in coarse root of DS indicated higher allocation to root to collect more h2o and nutrients from nutrient deficient soil.

Among unlike components of trees, foliage deemed highest percentage (43 % in United states of america and 42 % in DS) of tree NPP. Information technology was nigh like to the before findings for tropical forests (Hertel et al. 2009; Doughty et al. 2013). A global dataset of NPP allocation in tropical forests reported 34 % in canopy, 39 % in wood, and 27 % in fine roots (Malhi et al. 2011). Present data of Usa, excluding herb NPP, also showed almost same pattern of allocation (33 % canopy, 46 % woody tissue including fibroid root, and 21 % fine roots).

Higher allotment of NPP in shrubs of DS equally compared to that of The states may be due to open canopy created as a result of logging and lopping of trees. The higher NPP of herbs in US might be associated with higher moisture and nutrients due to accumulation of more litter on the soil. Fine root, although sharing a very small per centum to total plant biomass, is ane of the major belowground components of the NPP. In nowadays study, FRB shared less than one % to total biomass but contributed xix–20 % to total NPP. The estimated FRP in this study was within the ranges of i.1–6.2 Mg∙ha−1∙year–i for global tropical forests (Vogt et al. 1986).

Carbon budget and flux

Aboveground C storage in both stands was 82 % of the full stored in vegetation and 64–69 % of that stored in the stand (vegetation plus soil). These values compare with the aboveground storage of 83 % vegetation C and 51 % stand C in a dry out tropical forest in Republic of india (Singh and Singh 1991). Equally in other tropical forests, relatively higher contribution of aboveground parts to the stand C in present instance may exist due to the presence of large sized trees with wide canopy.

The contribution of aboveground (74–75 %) and root (25–26 %) parts to stand NPP in both forest stands is comparable to 72 % NPP for aboveground parts (Singh and Singh 1991). The college contribution of wood parts to the total C input equally compared to foliage in DS may be due to the lopping of branches and twigs. On the other hand, closed awning of trees in US accounted for higher input of foliage C compared to wood.

The transfer of C from foliage compartment to the litter compartment involved 100 % of herbaceous aboveground production plus 86 % of leaf product while the remaining corporeality, i.eastward., almost 14 % of foliage product did not find its manner into leaf litterfall. It happens due to the losses during senescence (Singh and Singh 1991).

Litterfall and FRB are important vectors of food recycling in forest ecosystems. Their turnover is usually determined by species, age groups, canopy cover, weather condition weather and biotic factors. Full C input into soil through litter plus root turnover was six.78 and iii.35 Mg∙ha–1∙year–1 in US and DS, respectively, suggesting substantial retentivity of C in the vegetation over in annual cycle (45 % in US and 51 % in DS). It indicates that the nowadays forest is C-accumulating system, acting as a pregnant global C sink, as other wet tropical forests (Pan et al. 2011).

Conclusions

The present study indicated that diverse types of anthropogenic disturbances have altered the structure and functioning of the economically important Sal-dominated forest. Although in having higher biomass, the NPP of present forest is relatively low indicating its maturity. Several disturbance activities like lopping, fodder drove, litter removal, grazing etc. result in the significant loss in stand biomass (53 %) and cyberspace production (44 %). Due to forest disturbance C stock and C sequestration capacity are reduced which reflects the higher C emissions. From the management point of view, better policy to reduce the C emission through vegetation should be formulated as per the objective of REDD+. In spite of this, both stands of this forest appear to human action every bit C-accumulating system, an important global C sink.

Abbreviations

- AGB:

-

aboveground biomass

- DS:

-

disturbed woods stand

- NPP:

-

cyberspace main product

- United states of america:

-

undisturbed wood stand up

References

-

Aragão LEOC, Malhi Y, Metcalfe DB, Silva-Espejo JE, Jiménez Due east, Navarrete D, Almeida Southward, Costa ACL, Salinas N, Phillips OL, Anderson LO, Alvarez Due east, Bakery TR, Goncalvez PH, Huamán-Ovalle J, Mamani-Solórzano M, Meir P, Monteagudo A, Patiño S, Peñuela MC, Prieto A, Quesada CA, Rozas-Dávila A, Rudas A, Silva JA Jr, Vásquez R (2009) Above- and below-ground net primary productivity across ten Amazonian forests on contrasting soils. Biogeosciences vi:2759–2778

-

Baral SK, Malla R, Ranabhat Southward (2009) Above-ground carbon stock cess in different wood types of Nepal. Banko Jankari 19:10–fourteen

-

Becknell JM, Kissing Kucek L, Powers JS (2012) Aboveground biomass in mature and secondary seasonally dry tropical forests: A literature review and global synthesis. For Ecol Manag 276:88–95

-

Beer C, Reichstein M, Tomelleri Due east, Ciais P, Jung M, Carvalhais N, Rodenbeck C, Altaf Arain M, Baldocchi D, Bonan GB, Bondeau A, Cescatti A, Lasslop K, Lindroth A, Lomas M, Luyssaert S, Margolis H, Oleson KW, Roupsard O, Veenendaal E, Viovy N, Williams C, Woodward FI, Papale D (2010) Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 329:834–838

-

Bombelli A, Henry Yard, Castaldi S, Adu-Bredu South, Arneth A, de Grandcourt A, Grieco Due east, Kutsch WL, Lehsten V, Rasile A, Reichstein M, Tansey Chiliad, Weber U, Valentini R (2009) The sub-Saharan Africa carbon balance, an overview. Biogeosci. Discuss half dozen:2085–2123.

-

Chave J, Olivier J, Bongers F, Châtelet P, Forget P-Thou, van der Meer P, Norden Northward, Riera B, Charles-Dominique P (2008) Above-ground biomass and productivity in a rain forest of eastern South America. J Trop Ecol 24:355–366

-

Chave J, Riera B, Dubois MA (2001) Interpretation of biomass in a Neotropical forest of French Guiana: Spatial and temporal variability. J Trop Ecol 17:79–96

-

Dixon RK, Solomon AM, Brownish S, Houghton RA, Trexler MC, Wisniewski J (1994) Carbon pools and flux of global forest ecosystems. Science 263:185–190

-

Djomo AN, Knohl A, Gravenhorst Yard (2011) Estimations of total ecosystem carbon pools distribution and carbon biomass current almanac increase of a moist tropical forest. For Ecol Manag 261:1448–1459

-

Doughty CE, Metcalfe DB, da Costa MC, de Oliveira AAR, Neto GFC, Silva JA, Aragão LEOC, Almeida SS, Quesada CA, Girardin CAJ, Halladay K, da Costa Air-conditioning, Malhi Y (2013) The production, allocation and cycling of carbon in a forest on fertile terra preta soil in eastern Amazonia compared with a forest on next infertile soil. Establish Ecol Diversity 7:41–53

-

Gautam TP, Mandal TN (2013) Soil characteristics in moist tropical wood of Sunsari district, Nepal. Nepal J Sci Tech 14:35–xl

-

Gibbon A, Silman MR, Malhi Y, Fisher JB, Meir P, Zimmermann M, Dargie GC, Farfan WR, Garcia KC (2010) Ecosystem carbon storage beyond the grassland–forest transition in the high Andes of Manu National Park, Peru. Ecosystems thirteen:1097–1111

-

Girardin CAJ, Espejob JES, Doughty CE, Huasco WH, Metcalfe DB, Durand-Baca L, Marthews TR, Aragao LEOC, Farfán-Rios Due west, García-Cabrera K, Halladay Thou, Fisher JB, Galiano-Cabrera DF, Huaraca-Quispe LP, Alzamora-Taype I, Eguiluz-Mora Fifty, Salinas-Revilla N, Silman MR, Meir P, Malhi Y (2014) Productivity and carbon resource allotment in a tropical montane cloud forest in the Peruvian Andes. Institute Ecol Diverseness 7:107–123

-

Hertel D, Moser Thousand, Culmsee H, Erasmi S, Horna Five, Schuldt B, Leuschner C (2009) Below- and in a higher place-footing biomass and net primary product in a paleotropical natural forest (Sulawesi, Indonesia) as compared to neotropical forests. For Ecol Manag 258:1904–1912

-

Ibrahima A, Mvondo ZEA, Ntonga JC (2010) Fine root production and distribution in the tropical rainforests of south-western Cameroon: furnishings of soil blazon and selective logging. iForest: Biogeosc For iii:130–136

-

Jenny H, Gessel SP, Bingham FT (1949) Comparative report of decomposition rates of organic matter in temperate and tropical region. Soil Sci 68:419–432

-

Kalembasa SJ, Jenkinson DS (1973) A comparative study of titremetric and gravimetric methods for the determination of organic carbon in soil. J Sci Nutrient Agri 24:1085–1090

-

Lü XT, Yin JX, Jepsen MR, Tang JW (2010) Ecosystem carbon storage and partitioning in a tropical seasonal forest in Southwestern China. For Ecol Manag 260:1798–1803

-

Malhi Y, Aragao LEO, Metcalfe DLB, Paiva R, Quesada CA, Almeida S, Anderson L, Brando P, Chambers JQ, Costa ACL, Hutyra Fifty, Oliveira P, Patino South, Pyle EH, Robertson AL, Teixeira LM (2009) Comprehensive assessment of carbon productivity, allocation and storage in three Amazonian forests. Glob Change Biol 15:1255–1274

-

Malhi Y, Doughty C, Galbraith D (2011) The allocation of ecosystem net chief productivity in tropical forests. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci 366:3225–3245

-

Malhi Y, Farfán Amézquita F, Doughty CE, Silva-Espejo JE, Girardin CAJ, Metcalfe DB, Aragão LEOC, Huaraca-Quispe LP, Alzamora-Taype I, Eguiluz-Mora L, Marthews TR, Halladay G, Quesada CA, Robertson AL, Fisher JB, Zaragoza-Castells J, Rojas-Villagra CM, Pelaez-Tapia Y, Salinas N, Meir P, Phillips OL (2014) The productivity, metabolism and carbon bicycle of two lowland tropical forest plots in south-western Amazonia, Peru. Constitute Ecol Variety 7:85–105

-

Mandal T (1999) Ecological analysis of recovery of landslide damaged Sal forest ecosystem in Nepal Himalaya. Dissertation, Banaras Hindu Academy, Varanasi

-

McBrayer JF, Cromack KJ (1980) Effect of snowpack on oak- litter breakdown and nutrient release in a Minnesota forest. Pedobiologia 20:47–54

-

Ngo KM, Turner BL, Muller-Landau HC, Davies SJ, Larjavaara M, Nik Hassan NF, Lum South (2013) Carbon stocks in primary and secondary tropical forests in Singapore. For Ecol Manag 296:81–89

-

Noguchi H, Suwa R, de Souza CAS, da Silva RP, dos Santos J, Higuchi Northward, Kajimoto T, Ishizuka M (2014) Examination of vertical distribution of fine root biomass in a tropical moist wood of the Fundamental Amazon, Brazil. Japan Agri Res Quarterly 48:231–235

-

Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Fang J, Houghton R, Kauppi PE, Kurz WA, Phillips OL, Shvidenko A, Lewis SL, Canadell JG, Ciais P, Jackson RB, Pacala SW, McGuire AD, Piao Southward, Rautiainen A, Sitch S, Hayes D (2011) A large and persistent carbon sink in the world's forests. Science 333:988–993

-

Powers JS, Becknell JM, Irving J, Pèrez-Aviles D (2009) Diverseness and structure of regenerating tropical dry forests in Republic of costa rica: Geographic patterns and environmental drivers. For Ecol Manag 258:959–970

-

Powers JS, Perez-Aviles D (2013) Edaphic factors are a more of import control on surface fine roots than stand up age in secondary tropical dry forests. Biotropica 45:one–9

-

Roderstein M, Hertel D, Leuschner C (2005) Above and beneath-ground litter product in three tropical montane forests in southern Ecuador. J Trop Ecol 21:483–492

-

Saner P, Loh YY, Ong RC, Hector A (2012) Carbon stocks and fluxes in tropical lowland dipterocarp rainforests in Sabah, Malaysian Kalimantan. PloS I 7. doi: x.1371/journal.pone.0029642

-

Singh JS, Singh SP (1992) Forests of Himalaya. Gyanodaya Prakashan, Nainital

-

Singh KP, Mandal TN, Tripathi SK (2001) Patterns of restoration of soil physciochemical backdrop and microbial biomass in unlike landslide sites in the sal forest ecosystem of Nepal Himalaya. Ecol Eng 17:385–401

-

Singh 50, Singh JS (1991) Storage and flux of nutrients in a dry tropical forest in Bharat. Ann Phytology 68:275–284

-

Singh SP, Adhikari BS, Zobel DB (1994) Biomass, productivity, leafage longevity, and wood structure in the Fundamental Himalaya. Ecol Monogr 64:401–421

-

Srivastava SK, Singh KP, Upadhyay RS (1986) Fine root growth dynamics in teak (Tectona grandis Linn. F.). Tin can J For Res sixteen:1360–1364

-

Vogt KA, Grier CC, Vogt DJ (1986) Production, turnover and nutrient dynamics of above and belowground detritus of world forests. Adv Ecol Res 15:303–377

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Caput, Department of Botany, Post Graduate Campus, Tribhuvan University, Biratnagar, Nepal for providing laboratory and library facilities. First author is thankful to the University Grants Committee, Nepal for Scholarship. Our heartfelt cheers go to Mr. KP Bhattarai who helped in data collection and laboratory assay.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TP carried out field and laboratory works, analyzed data, designed and drafted the manuscript. TN designed and supervised the research. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

i) TP participated in this research as a doctoral student. At present, he is working as Associate Professor in the Section of Botany, Mahendra Morang Adarsha Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University, Biratnagar, Nepal.

2) TN is a professor of Botany in Post Graduate Campus, Tribhuvan Academy, Biratnagar, Nepal.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gautam, T.P., Mandal, T.Due north. Upshot of disturbance on biomass, product and carbon dynamics in moist tropical woods of eastern Nepal. For. Ecosyst. three, 11 (2016). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s40663-016-0070-y

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-016-0070-y

Keywords

- Tropical forest

- Disturbance

- Biomass

- Product

- Carbon cycling

- Nepal

Source: https://forestecosyst.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40663-016-0070-y

0 Response to "What Percent of the Biomass Produced in a Forest Is Returned to the Soil?"

Post a Comment